Pop Civ 21: Marbury to Brown

Introduction

With a new school year already begun, we’re excited to share a new teacher lesson plan that examines the role of judicial review on our three branches of government since the time of the Marshall Court.

Ask any elementary student about our nation’s three branches of government, and you should hear about “checks and balances” designed to keep our legislative, executive, and judicial bodies from becoming too powerful. But how exactly does each branch of government actually exert its power? And how do the principles put into place in the early Republic connect with the decisions made by legal heavyweights in the 20th and 21st Centuries?

Historical Context

In the early 1800s, the United States of America was still figuring out how its newborn government would function. Following the contentious election of 1800, outgoing President John Adams hoped that his defeated Federalist party could retain power by appointing like-minded judges to vacant federal court seats. Just days before President Thomas Jefferson took office in 1801, Adams named 60 Federalists to fill those positions. These “Midnight Judge” appointments required the physical delivery of handwritten commissions to the nominees, and some deliveries had not been made as Jefferson’s first term began. Jefferson ordered his Secretary of State, James Madison, not to deliver the commissions to the Federalist judges. This left Adams’s appointees without the documentation required to take their positions on the bench.

Once such appointee was William Marbury. He filed suit against Secretary Madison, and the case eventually came before the Supreme Court. Marbury wanted the Court to order a writ of mandamus, forcing Madison to deliver the commissions as promised by President Adams. The plaintiffs in the case, Marbury v. Madison, argued that the Judiciary Act of 1789 empowered the Supreme Court to compel government officials to fulfill their duties.

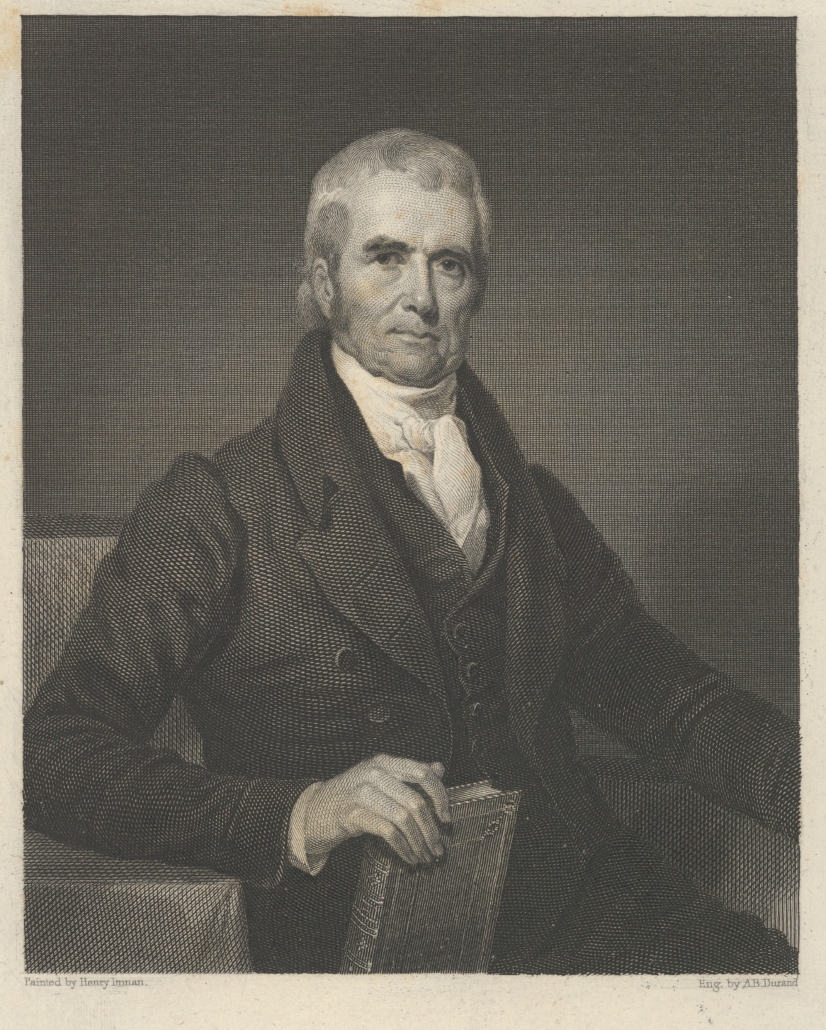

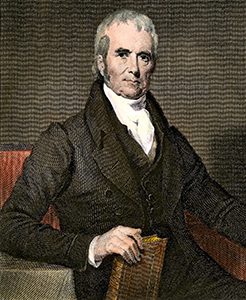

Presiding over the Court as Chief Justice was John Marshall, a Federalist and former member of the Adams Administration. Chief Justice Marshall looked beyond partisan perspectives to evaluate the constitutionality of three questions before the Court. First, did Marbury and the other plaintiffs have a right to receive their commissions; secondly, could they sue for their commissions in court, and lastly, should the Supreme Court order the delivery of their commissions based on the Judiciary Act of 1789?

Chief Justice John Marshall

In a unanimous decision, the Court determined that the plaintiffs did have a legal right to their commissions, and that Madison’s decision to withhold them was illegal. But the Court refused to issue a writ of mandamus, and asserted that the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional, since it violated the provisions laid out for the powers of the Judiciary in Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution.

By issuing this opinion, the Marshall Court confirmed a fundamental understanding for the American legal system: that the judicial branch would be the ultimate arbiter of whether a government action was constitutional. This understanding was established with 1796’s Hylton v. United States, the first case decided by the Supreme Court that involved a direct challenge to the constitutionality of an act of Congress. The Court reviewed the Carriage Act of 1794, and evaluated whether the direct tax it proposed was constitutional. The court found the “carriage tax” constitutional.

The concept of “judicial review” empowered the judiciary to serve as a check on the executive and legislative branches by evaluating the constitutionality of laws passed by congress or enacted through executive action. The impact of this decision cannot be overstated; it was essential in establishing the three branches of the U.S. government as co-equal to one another. More than 150 years later, the Supreme Court again relied on the concept of Judicial Review when evaluating the legality of another national issue.

In Brown v. Board of Education, the Court evaluated whether racially segregated and “separate but equal” schools violated the 14th Amendment of the Constitution. Laws imposing racial segregation in public places stood in many states, some even dating to a time before the Court’s 1896’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. That landmark case ruled that racial segregation was constitutional as long as the segregated accommodations were “equal.” The plaintiffs in Brown argued that those laws violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, and brought their suit to the Supreme Court for evaluation.

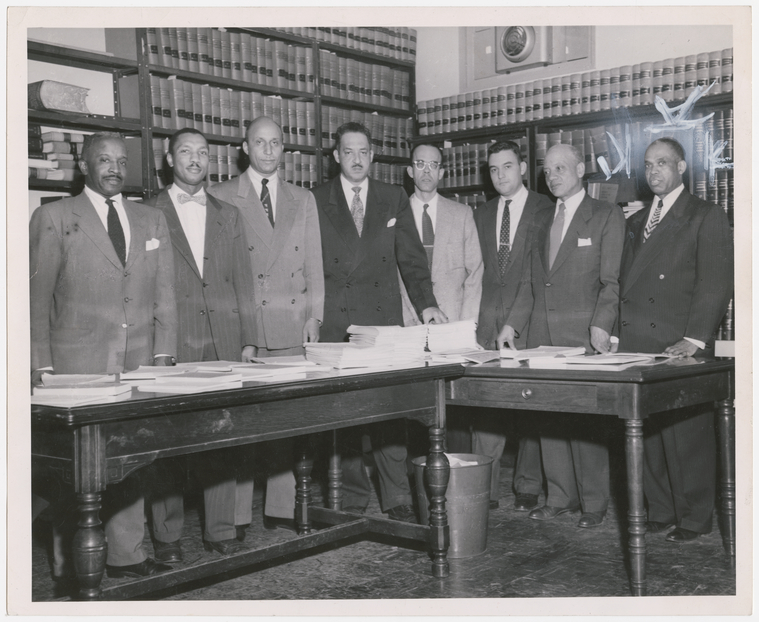

Thurgood Marshall (fourth from left) and other members of the N.A.A.C.P. legal defense team who worked on the Brown v. Board of Education case. Courtesy NYPL.

The Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, unanimously decided to reject the “separate but equal” doctrine that had held since the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, decreeing that not only was segregation in schools unconstitutional but also ordered segregated Southern states to integrate their schools with “all deliberate speed.” While Southern states, including Virginia, fought school integration for years to follow, the concept of legal segregation had been eradicated from American law.

On the surface these two cases seem unconnected to one another, they are linked by the thread of the power of judicial review. When deciding the fate of the Midnight Judges’ futures in 1801, the Justices of the Marshall Court couldn’t have anticipated the future importance of their decision to establish the principle of judicial review. But had they not done so, the Justices of the Warren Court would have been unable to evaluate the constitutionality of states’ segregation laws and order the end of state-sanctioned racial segregation.

Judicial Review Basics

Explore Further

Now that you’ve learned a little background on how Marbury v. Madison and Brown v. Board of Education are connected by the principle of judicial review, dive deeper and explore our new JMC lesson plan: