Pop Civ 19: What Exactly is a Shadow Docket?

Introduction

On April 6, 2022, the Supreme Court issued a 5-4 opinion that reinstated a policy from the Trump administration that restricted states’ ability to regulate how projects might impact water quality in their jurisdiction. The decision, unsigned and without any accompanying explanation, prompted a dissent from Justice Kagan that was signed by three other Justices, and was joined by the Chief Justice, John Roberts. It was issued under the emergency, or shadow docket, which made us want to know – what is the Court’s shadow docket, and how does it work?

The Court’s Various Dockets

The term “Shadow Docket” was first coined in 2015 by William Baude, professor at the University of Chicago Law School but describes a Supreme Court process that has been in place for decades. Before we dive into the specifics of that docket’s current usage, we should note that Baude initially used the term “shadow docket” because the cases being decided were typically low profile and remained in the shadows, away from public attention. That has changed during the Trump administration; while we still use the term “shadow docket” in this post, one could also refer to this process as the “emergency docket” or “non-argument” docket. Additionally, the term “shadow docket” carries a negative connotation that some opponents of the way the docket is being implemented use to their advantage when making their critiques.

The cases that most Americans are aware of moving through the Court are those heard on its “merits docket,” which follow a set of ordinary procedures as they are being considered. A case is added to the merits docket when at least four Justices agree that it has sufficient merit to be heard by the Court. Petitioners and respondents then file briefs on the case, which the Justices and their clerks use to prepare for the case’s oral arguments. After hearing those arguments, Justices enter into conference, discussing each case and making assignments for opinions. Finally, opinions are announced and handed down to the public. (To read more about a year in the Supreme Court, visit our Pop Civ post on the 2020 October Term.)

In our digital age, each step of this standard process is made as accessible as possible to the public. Before decisions are made, briefs are posted on the Supreme Court’s website, as are audio recordings of oral arguments. Once opinions are handed down, they are available for immediate access by the public.

And we pay attention when high-profile cases are before the Court. Media outlets often cover oral arguments in cases that handle controversial issues, or film the running of the interns when a landmark case’s opinion is handed down. But these noteworthy cases represent a fraction of the Court’s operations. While only 70 or so cases will have oral arguments before the Court each year, thousands of unsigned opinions and orders are issued through the shadow docket. Because these typically relate to unremarkable issues, they receive far less media attention and tend to go unnoticed by the general public.

In recent years, however, there has been a shift in the way the Court uses one function of the shadow docket. Occasionally, the Court is asked to provide immediate relief in a case that has been heard by a lower court while the appeal is making its way to the Supreme Court. As an example: in 2021, a district court remanded and vacated a stay from a lower court regarding a Tump administration rule that tightened an Environmental Protection Agency process governing federal permits for projects that might impact “waters of the United States.” In short, companies could receive waivers that allowed them to avoid obtaining certification that their work would not cause harm to state waterways. In 2020, a District Court vacated the Trump administration’s rule, and an appeal failed to yield a stay. Petitioners asked the Supreme Court to issue a stay which would reinstate the Trump-era rule. One note: applicants seeking emergency relief from the Court must illustrate how lack of immediate action from the Court would cause them “irreparable harm.”

On April 6, 2022, a decision was issued through the shadow docket granting the stay, our lead example. That order was unsigned and was accompanied by no reasoning from the Justices as to why they decided to grant the stay. The Trump-era EPA rule is back in effect, but legal scholars, lower court judges, and attorneys have no written decision to help understand how to interpret the order. In her dissent, Associate Justice Elena Kagan argued that there was not sufficient evidence to suggest that the petitioners would face irreparable harm if the Court did not issue an emergency decision. She continued:

“By nonetheless granting relief, the Court goes astray. It provides a stay pending appeal, and thus signals its view of the merits, even though the applicants have failed to make the irreparable harm showing we have traditionally required. That renders the Court’s emergency docket not for emergencies at all. The docket becomes only another place for merits determinations—except made without full briefing and argument. I respectfully dissent.”

Justice Elena Kagan (left) and Justice Samuel Alito (right)

This lack of transparency is central in the criticism some legal scholars have raised with the Court’s increased use of the shadow docket. The legal community relies on the extensive content of the Court’s written opinions to parse the meaning of its decisions. How precedent should be applied is often reliant on the Justices’ arguments in support of or opposition to a decision from the Court. But in the shadow docket cases, no supporting information exists to help members of the legal profession interpret the Court’s actions.

And yet others find the criticism of the shadow docket’s emergency applications to be baseless. Speaking at a lecture at Notre Dame, Associate Justice Samuel Alito explained his perspective:

“The catchy and sinister term ‘shadow docket’ has been used to portray the court as having been captured by a dangerous cabal that resorts to sneaky and improper methods to get its way. And this portrayal feeds unprecedented efforts to intimidate the court or damage it as an independent institution.”

Justice Alito and others assert that the Court has always needed to use its emergency docket to provide immediate relief to applicants. Furthermore, they argue that the most vocal critics of its current use are those who disagree with a particular decision. Rather than critique the opinion itself, they argue, disgruntled opponents launch attacks on the process.

Regardless of how the Court continues to use its emergency docket in the future, one thing is certain: the public is now significantly more aware of its use than in previous decades. In February of 2021, the House Committee on the Judiciary held a hearing to investigate the shadow docket’s use (use the link below to see the footage from the hearing), meaning that congressional attention is also tuned into its operations.

How the Shadow Docket Functions

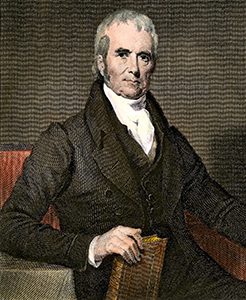

Justice William O. Douglas and the Shadow Docket

Justice William O. Douglas. Courtesy Library of Congress.

While emergency docket orders are often unsigned, two notable cases from the 20th century feature emergency orders issued by the same member of the Court, Associate Justice William O. Douglas.

Appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 to replace the Justice William Brandeis, Justice Douglas was a mere 40 years old when he was confirmed to the bench. Known for his staunch liberal leaning and a belief that the Court was not meant to be impartial, Douglas served for 36 years on the Court, and was author of more opinions than any other Justice in Supreme Court history.

The first of the two cases in which Douglas intervened was in the 1953 execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, two Americans working as spies for the Soviet Union during World War II. After being found guilty of sharing atomic secrets with the Soviets, the Rosenbergs were slated for execution on July 18. On July 17, Justice Douglas issued an emergency stay, arguing that a jury was required to issue the sentence of death in the Rosenberg’s case, which did not happen. The U.S. Attorney General appealed to the Chief Justice, Fred M. Vinson, who reconvened the Court to vacate the stay. The Rosenbergs were executed on July 19 by electric chair at Sing Sing prison in New York.

Twenty years later, Douglas again intervened in a high-profile matter by issuing another emergency order. In 1973, U.S. House of Representatives member Elizabeth Holzman brought suit against the Nixon administration for its bombing campaign in Cambodia. Holzman argued that the executive branch had exceeded its authority by launching an offensive in Cambodia without Congressional support. After a lower court issued an injunction to prevent the bombing, the Court of Appeals issued a stay of that order. Holzman applied to Justice Thurgood Marshall, hoping that he might overturn the stay, but Marshall refused the appeal. Finally, Holzman lobbied Douglas, who issued an order requiring the military to cease its bombing. The military ignored the order, and only six hours later, Justice Marshall convened the seven other Justices by telephone to issue a unanimous ruling overturning Douglas’s order.