The Great Chief’s Great Love

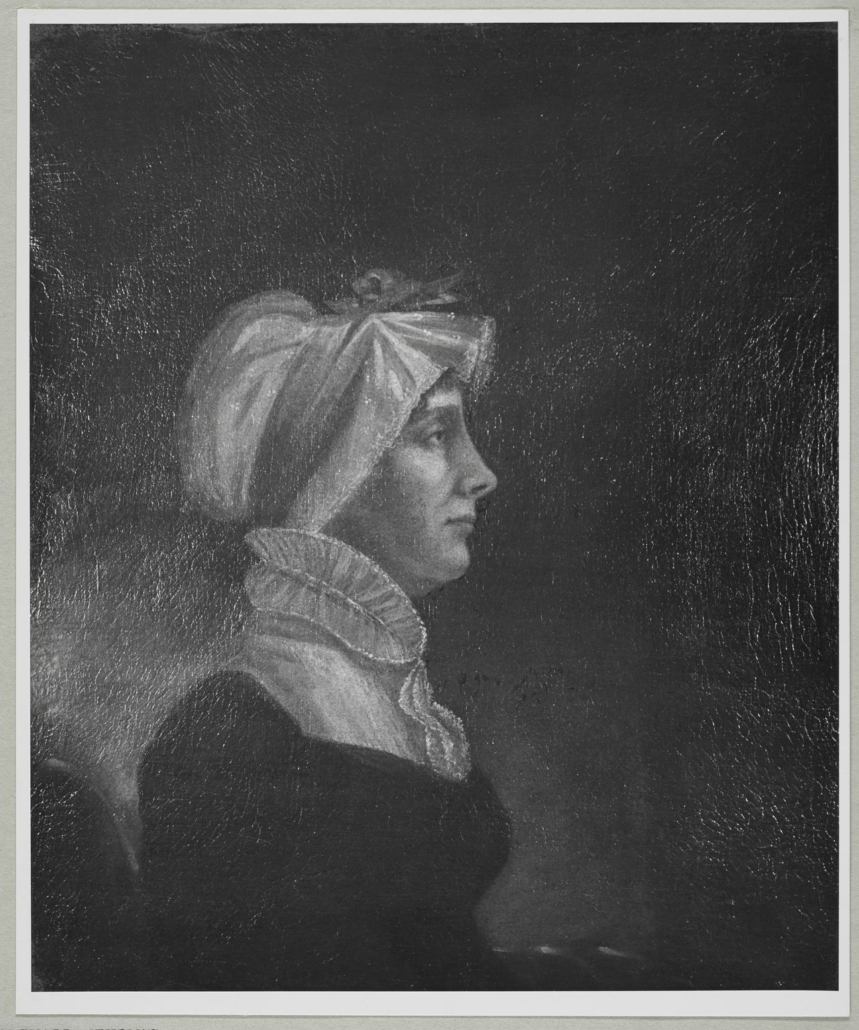

Mrs. John Marshall (Mary Willis Ambler), c. 1804.

Introduction

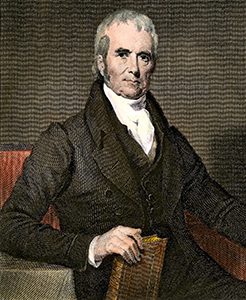

As Women’s History Month draws to a close, we’re taking a moment to remember a woman near and dear to John Marshall’s heart: his wife, Mary “Polly” Ambler Marshall. What impact did this very private woman have on her very public husband? What did it mean to be a woman of status at the turn of the 19th century? Read below to learn a little more about the Great Chief Justice’s greatest love.

My Dearest Polly

Born in 1766, Polly Willis was the second of five girls born into the wealthy Ambler family of Yorktown, Virginia. Her father, Jaquelin Ambler, was a merchant and planter who rose to prominence during the Revolutionary era.

As a member of a well-to-do family, Polly’s upbringing and education would have been focused on preparing her to be a mother and wife in the same social circles her parents occupied. Polly would have learned basic writing, reading, arithmetic, and religious principles from her mother, Rebecca Burwell. As a girl, she would also have been aware of her eventual role as the manager of her own household after marriage. Wealthy 18th-century women oversaw the running of their family’s households, which, in Virginia, meant managing the enslaved men and women who did the labor required to keep a home clean, fed, and running smoothly.

And yet, Polly’s preteen years were surely unusual; the year she turned ten, the Declaration of Independence was signed, and the thirteen American colonies waded into war with Great Britain. Although women were not typical fixtures on the front lines, wealthy families like the Amblers would have made an effort to support the war effort on the home front. For example, Virginia matrons boycotted teas imported by the British, instead finding inspiration for teatime in their gardens. Women served “Liberty Tea” made of herbal ingredients like rosehips, peppermint, and lavender at their social gatherings in a sign of solidarity with the Revolutionary cause.

By the time she turned 14, Polly had met the man that she would eventually marry. John Marshall, a 25-year-old Continental soldier on military leave, came to visit family in Yorktown. There, he met a young Polly, and described her thus:

“I saw her first the week she attained the age of fourteen & was greatly pleased with her. Girls then came into company much earlier than at present.”

John and Polly would cross paths at dances in the following months, and John began to court Polly in earnest. In 1782, John proposed marriage to Polly, who, according to family lore, responded with a flustered “no” despite wanting to accept. Her cousin hastily acted as a go-between to reassure John that Polly was, in fact, willing to marry him. The two wed in 1783.

Motherhood would prove bittersweet for Polly. The Marshall’s first son, Thomas, was born in 1784, and a second son, Jaquelin, followed in 1787. But following his birth, Polly experienced two miscarriages and lost two infant children before successfully carrying her third child, Polly, to term in 1795. Infant mortality at the turn of the 18th century was significantly higher than today; in the new United States, more than 40 percent of children born would not live to see their fifth birthday. Miscarriage, too, was a heartbreakingly common occurrence, but one rarely discussed beyond the cloistered conversations of women.

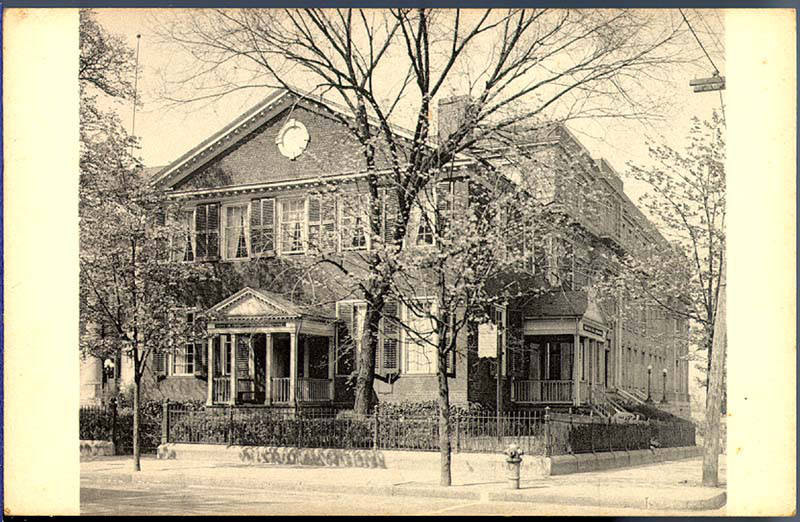

The Marshall House, Richmond VA. Courtesy VCU Libraries.

Family lore told of Polly’s deteriorating health and mental state following the losses of their children. Through a modern-day lens, one can easily understand why such devastating events might have a profound impact on a woman’s life. At the time, however, Polly’s struggles would have been brushed aside as a typical part of the childbearing process. Polly herself did not leave behind any written record of this period of her life; the heartbreak she experienced would have been, like that of many women of the era, a wholly private affair. Ultimately, six Marshall children would survive childhood: Thomas, Jaquelin, Mary, John, James, and Edward.

In 1790, the Marshall family took up residence at a new home built in the fashionable Court End neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia. This would be the main residence for the couple until both of their deaths, and was seen as “plantation-in-town.” Its grounds included Marshall’s law office, a laundry, stables, kitchen garden, and the family’s main residence. Like its rural counterparts, a city property like the Marshalls’s would have depended on the labor of enslaved men and women to function efficiently; the only difference would have been in scale. Polly would have had dominion over the running of the residence and of its associated enterprises (laundry, kitchen, and similar domestic spaces), but would have overseen a staff of skilled enslaved staff who would have executed the work, including the rearing of the Marshall children. The John Marshall House is open to the public, owned and operated by Preservation Virginia, and contains an impressive collection – the largest anywhere – of original Marshall Family objects.

For the next several decades, most of what we know of Polly’s life is gleaned through the letters written to her by John. A lively correspondent, John wrote to her often and with vibrant language; sadly, her replies do not survive. Through his missives, however, we can piece together a picture of a woman who spent much of her time either at home in Richmond, or traveling in pursuit of cures for her various physical ailments. John traveled extensively, both within the new nation and abroad as a diplomat and as Secretary of State under President John Adams, and then as the nation’s Chief Justice. Polly’s focus narrowed not just to the family homes in Richmond and other rural properties around Virginia, but often to the confines of rooms within those homes when her ill health kept her in bed.

How Polly felt about her husband’s rise to prominence historians will never know. John wrote warmly to his “Dearest Polly” (as he always addressed her in his letters) about the many exciting events of his professional life outside of Richmond, but often mentions his concern for her health and happiness in the same letters. Polly died on Christmas Day in 1831, a devastating loss for John. On the first anniversary of her death in 1832, he wrote:

“On the 25th of December 1831 it was the will of Heaven to take to itself the companion who had sweetened the choicest part of my life, had rendered toil a pleasure, had partaken of all my feelings & was enthroned in the inmost recesses of my heart. Never can I cease to feel the loss & to deplore it. Grief for her is too sacred ever to be profaned on this day, which shall be during my existence devoted to her memory.”

Polly was buried in Shockoe Hill Cemetery and visited by John on walks there from his Court End home.

John and Polly’s graves in Shockoe Hill Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia.

Women in the New Republic

Polly and the Petition

Given her preference for privacy and seclusion, it it surprising that one of the few documents that bears Polly’s name is connected to the murder trial of a free Black woman in Richmond.

In 1792, Angela Barnett (sometimes called Angelica and Angelia in records) was a free woman of color living in Henrico County near the Richmond City limits. Under suspicion that she was harboring enslaved runaways, two white men, Peter Franklin and Jesse Carpenter, stormed into Barnett’s house intent on confronting her. Upon entry, Franklin charged at Barnett with a weapon in hand. Fearing for her life, Barnett grabbed an adze lying near and swung at Franklin, who fell to the ground mortally wounded. Barnett was subsequently arrested, charged with Franklin’s murder, and found guilty in 1793.

Although Barnett would have occupied a lower status within Richmond society as a Black woman, she had forged powerful connections with members of the city’s elite community through her work within their homes. Upon learning of her death sentence, a group of Barnett’s former employers and acquaintances penned a petition for mercy to the Governor, Henry Lee, asking for clemency on her behalf. Among the signatories was Polly Marshall.

Another unique element of this petition was that all but two of its signatories were women. Matrons in the Richmond gentry would typically have recoiled at the request to engage in the public scandal surrounding the case. Perhaps the strength of the relationships Barnett established in caring for their children, cooking their food, and tending to their personal needs motivated these women to speak out on her behalf.