Pop Civ 16: American Abortion Rights and Judicial Review

Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the clinic at the center of the case being considered by the Supreme Court. Image courtesy Jackson Free Press.

Introduction

In the nearly fifty years since the Supreme Court issued its opinion in the landmark Roe v. Wade case, Americans have continued to hotly debate the legality of abortion. Political parties center the issue in their election campaigns, researchers regularly question Americans about their views in nationwide polls, and candidates nominated to the Supreme Court are asked to share their perspective on the constitutionality of Roe in their confirmation hearings.

In this year’s October Term, the Supreme Court considered two cases which may fundamentally change how the nation regulates access to abortions. The more significant of the two cases, Dobbs v. Jackson County Women’s Health, centers around a 2018 Mississippi State law that restricts abortions after fifteen weeks, regardless of extenuating circumstances. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the state’s only clinic that provides abortion services, has sued in federal court requesting a Temporary Restraining Order blocking the law. Mississippi is asking that the Court revisit whether individual states have the right make decisions about access to abortion at the local level.

Should the Court decide in Mississippi’s favor, the decades-long history of legal abortions in the United States would change. A major part of that change would take place in states with so-called “trigger laws,” which are designed to kick into effect the moment Roe v. Wade ceases to be upheld. Additionally, the Court is weighing whether states have the power to challenge federal law, especially those upheld as constitutional by the Supreme Court – in essence, does the principle of judicial review that was established in the Marshall Court continue to hold the power it has since Marshall’s time.

Abortion Access and the Courts

While America’s relationship with abortion rights dates to its founding, the modern history of abortion law centers around 1973’s Roe v. Wade. An anonymous woman, Jane Roe, brought suit against the District Attorney of Dallas County, TX, to challenge an existing state law that prohibited abortion except in instances where a woman’s life was at risk. In a 7-2 decision for Roe, the Supreme Court held that a woman’s right to privacy, including her right to decide to have an abortion, was protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. While the state could impose restrictions on abortions to protect the “potentiality of human life” of the fetus during the second and third trimesters, it could not do so during a woman’s first trimester of pregnancy. The ruling struck down state laws that prohibited abortions and made first-trimester abortions legal across the United States.

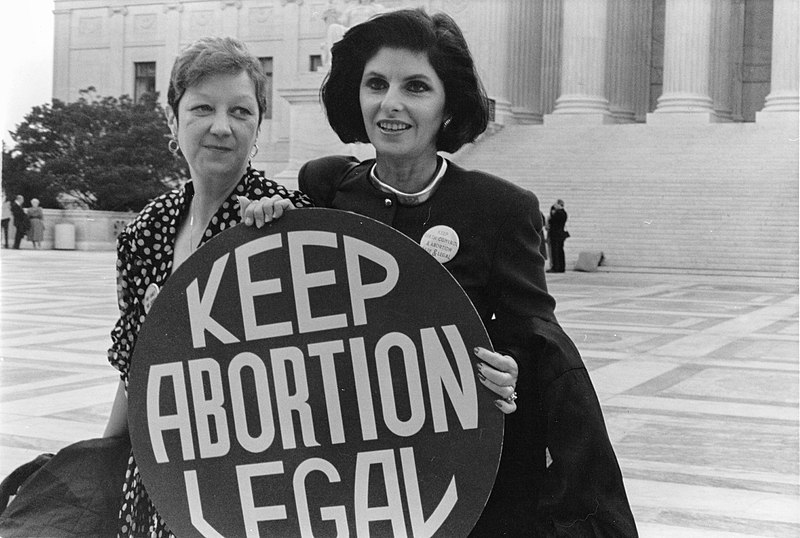

Norma McCorvey (Jane Roe) and her lawyer Gloria Allred on the steps of the Supreme Court, 1989. Courtesy Lorie Shaull.

In 1992, the Court reaffirmed its ruling on Roe with its decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. In a close 4-5 decision, the Court reiterated that the Constitution protected a woman’s right to an abortion, and implemented a new standard to determine whether state laws restricting abortion access placed an “undue burden” on the woman seeking the procedure.

Nearly twenty years after that ruling, the Court is again considering cases that would significantly impact the existence of Roe. In November, Justices heard oral arguments in Whole Women’s Health v. Jackson, a case focused on a Texas law that prohibits abortions after six weeks. In addition, the law includes a provision permitting members of the public –rather than state agents – to file suit against anyone who “aids and abets” the acquisition of an abortion, including doctors who perform such procedures and even Lyft or Uber drivers who transport a woman seeking an abortion. In a 5-4 decision issued on December 10, 2021, the Court permitted the Texas ban on abortions to stand but has allowed a narrow portion of the case to continue, in which abortion providers may sue the Medical Licensing Board. Those providers may not sue state clerks, judges, or the Texas Attorney General.

The second case being considered in this October Term, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is forcing the Court to again weigh in on the constitutionality of abortion prohibitions based on a fetus’s “viability.” Enacted in 2018, the Mississippi “Gestational Age Act” outlawed abortions in the state after fifteen weeks; Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Mississippi’s sole licensed abortion provider, filed suit seeking an emergency temporary restraining order. The district court decided that Mississippi had not provided sufficient evidence to support the claim that a fetus is, in fact, viable after fifteen weeks, and the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed that decision. Oral arguments were heard by the Supreme Court on December 1, and a decision has yet to be issued.

While the nation waits impatiently for a decision to be issued in Dobbs, many around the country are expressing a renewed interest in their states’ stance on abortion. Should the Court overturn Roe v. Wade, the issue would become one adjudicated at the state level; laws regarding abortion access can vary widely, even between two adjacent states. Some local governments have enacted “trigger laws,” which would limit or completely ban abortion upon Roe’s repeal, while others regarding abortion access would remain unchanged.

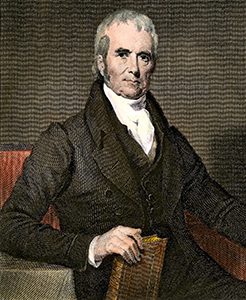

In addition to shouldering the weight of this deeply personal and sensitive topic, Justices are also being asked to evaluate how the Court itself should function as it evaluates the constitutionality of local laws. During the December 1 oral arguments for Dobbs, Justice Sotomayor responded to the Solicitor General of Mississippi by citing Marbury v. Madison, where Chief Justice John Marshall helped establish the principle of judicial review:

“Counsel, there’s so much that’s not in the Constitution, including the fact that we have the last word. Marbury versus Madison. There is not anything in the Constitution that says that the Court, the Supreme Court, is the last word on what the Constitution means. It was totally novel at that time. And yet, what the Court did was reason from the structure of the Constitution that that’s what was intended. […] I fear none of those things are written in the Constitution. They have all, like Marbury versus Madison, been discerned from the structure of the Constitution. Why do we now say that somehow Roe versus Casey is – Roe and Casey are so unusual that they must be overturned?”

Chief Justice John Roberts also hearkened back to the Marshall Court in his opinion in Whole Women’s Health v. Jackson, warning that state laws like Texas’s S.B.8 would delegitimize the authority of the Court:

“The clear purpose and actual effect of S. B. 8 has been to nullify this Court’s rulings. It is, however, a basic principle that the Constitution is the “fundamental and paramount law of the nation,” and “[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 177 (1803). Indeed, “[i]f the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery.”

Anti-abortion activists at the 2015 annual March for Life in Washington, D.C.