Pop Civ 12: An Independent Judiciary

Introduction

American students generally learn about the three branches of our government. Most Virginia fourth graders can rattle off their executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, and can state that each is intended to provide checks and balances on the other.

But how, exactly, does that system of balance work? Does today’s judicial branch have anything in common with the ideas sketched out in the Constitution? And how did John Marshall’s vision for an American Judiciary evolve over the last three centuries? We’ll dive into these questions and more in our exploration of an independent American Judiciary.

Establishing the Judiciary

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, founders debated how the judiciary should be structured. That it should be separate from the executive and legislative branches was clear, but how would it function in relation to the other two branches? Should there be a Supreme Court, and if so, how would it interact with lower courts? How much should judges be paid?

Rather than resolving these questions at the Convention, the framers sketched a rough structural outline for the federal judiciary in Article III of the Constitution. Congress would then be called upon to hash out the details of that judiciary.

The Annals of Congress, Senate, 1st Congress, 1st Session, describing the “Judicial Act” being debated. For more documents, visit the Library of Congress’s Research Guide for the 1789 Judiciary Act

By 1789, the First Congress was considering a Judiciary Act, drafted by Connecticut Senator Oliver Ellsworth. In the Act, a three-tiered judicial branch is proposed, with lower courts, circuit courts, and a Supreme Courts in ascending levels of power. The Supreme Court would have a chief justice and five associate justices, and would be empowered to review and decide cases heard in the lower courts. In September of that year, the Act passed both houses of Congress, and President George Washington signed it into law. Through the following two centuries, the judiciary would undergo some changes to its structure and function, but much of the framework of our modern judiciary is unchanged from the vision set out in the 1789 Act.

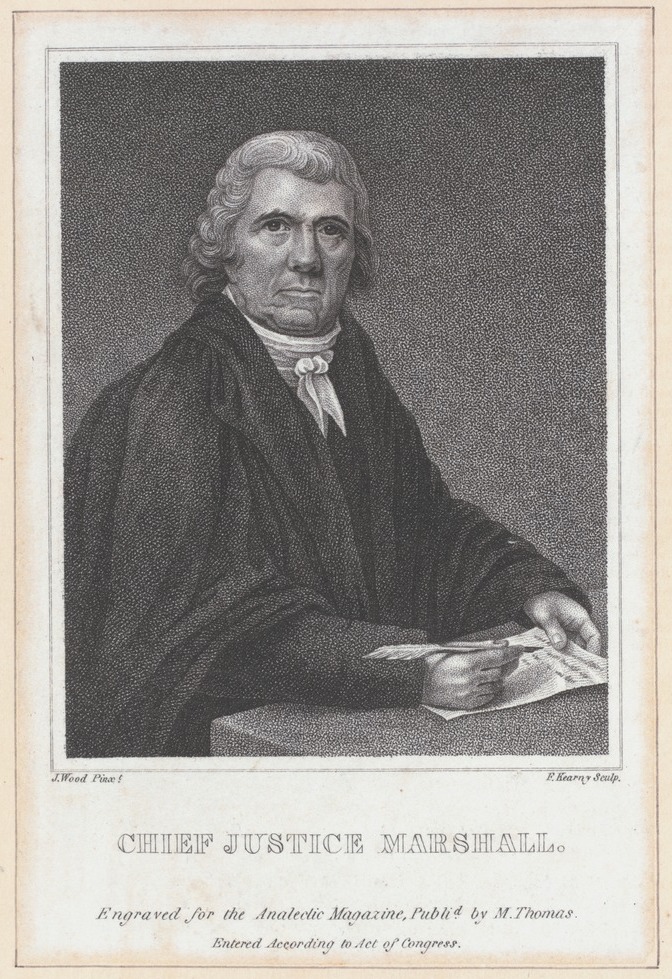

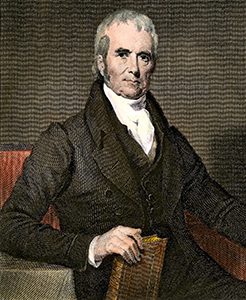

In 1801, John Marshall had been named Chief Justice by President John Adams. While he was not the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, Marshall is the individual responsible for shaping the Court’s powers in ways that still resonate today. Most significantly, Marshall’s decision in 1803’s Marbury v. Madison established the Judiciary’s ability to check its sister branches of government, asserting its right to judicial review. Based on Marshall’s opinion in Marbury, the judiciary assumed the power to evaluate the constitutionality of executive and legislative acts. In short, the judiciary could overrule an action of the executive or legislative branches if that act violated the Constitution. By establishing this power, Marshall ensured that the Court could serve as a crucial check on the executive and legislative branches, and established the judiciary as a truly co-equal branch of government.

Chief Justice Marshall, engraving by Francis Kearney. Courtesy New York Public Library.

The Judiciary would exercise this power frequently in the following two and a half centuries. In 1819, the Supreme Court heard McCullough v. Maryland and was asked to evaluate whether the Constitution permitted Congress to establish a federal bank, and whether the State of Maryland could levy taxes against said bank. The Court, with Marshall still presiding as Chief Justice, unanimously decided that Congress could, in fact, establish the bank. The majority opinion stated that the Constitution could be interpreted as giving Congress “appropriate and legitimate” powers not explicitly laid out in text, which was central in establishing federal authority over the States.

With the benefit of hindsight, 21st-century Americans can also point to moments in judicial history when the courts hindered the growth of the nation. Dred Scott v. Sanford of 1857 is a notorious example of such a moment. In that case, the Court found that enslaved or free Africans could not be considered American Citizens, and that enslaved people were the legal property of their enslavers based on the Fifth Amendment. Additionally, the Court ruled that an enslaved person who had relocated to a free state was not emancipated simply because that individual had reached a location where slavery had been abolished. As a result, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, a legislative act, was rendered unconstitutional, and the rights of enslavers were elevated above those of the men, women, and children they held in bondage. Not only did that decision endanger the lives of escaped Africans living in free territories, it exacerbated an already volatile relationship between pro- and anti-slavery factions within the government.

Throughout our history, the Court has also been asked to weigh in on a President’s right to issue wartime Executive Orders. In 1952, during the height of the Korean War, President Harry Truman ordered the Secretary of Commerce to take control of several steel mills across the country. One such company, Youngstown Sheet & Tube, sued to determine whether this was constitutional or not.

Later that same year, the Supreme Court heard Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company v. Sawyer, where it decided 6-3 that the President could not take control of a private company simply because of a national war effort. Furthermore, the Court asserted that “the President’s power to see that the laws are faithfully executed refutes the idea that he is to be a lawmaker.”

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Company postcard.

Almost a century after Dred Scott, the Court’s right to judicial review allowed for a massive expansion of rights for Americans. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court was asked to consider whether segregation in schools was permissible under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court unanimously decided that the “separate but equal” conditions that existed in segregated schools directly violated the 14th Amendment, and as a result, districts across the nation were ordered to integrate their student bodies. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Warren chose to use language that was simpler and more direct that typical written opinions, as he felt that the Court’s decision was one that all Americans should be able read and understood.

More recently, 2012’s United States v. Alvarez serves as an example of how the Court could simultaneously impact both the Legislative and Executive branches with a single decision. In 2005, Congress passed the Stolen Valor Act, which sought to punish individuals who falsely claim to have been awarded high military honors. In United States v. Alvarez, the Court was asked to decide whether Xavier Alvarez’s First Amendment rights were being violated when he was charged with two counts of misrepresenting himself under the Stolen Valor Act. In a 6-3 decision, the Court ruled that the Stolen Valor Act was written too broadly, and that Congress had no right to impose criminal punishment for the type of speech made by Alvarez. Shortly following the Court’s decision, the President (supported by the Pentagon) established a database of medal citations to help verify who had rightfully received military honors. Following the creation of that database, Congress amended its original Act with the Stolen Valor Act of 2013, remedying the sections of the 2012 Act that violated the Constitution.

An Independent Judiciary

Pop Culture in the Courtroom

Usually our PopTriv sections look at how the courts have found their way into movies, film, or television. But what happens when pop culture worms its way into the day-to-day operations of the courts? In particular, does the weight and responsibility of judicial review suffer when its judges decide to use cultural references in their opinions?

In June of 2021, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Kenneth Lee issued an opinion in the Briseño v. Henderson case, a class action suit that was sent back to the lower court. Judge Lee began his opinion thus: “We can perhaps sum up this case as ‘How to Lose a Class Action Settlement in 10 Ways.’”

Following this wordplay based on the title of the popular film, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days (starring Kate Hudson and Matthew McConaughey) the judge doubled down on the pop culture references by explaining that the courts should not second guess class settlements just because a party professed that “their dubious deal is ‘all right, all right, all right,’” using McConaughey’s signature line from the 1993 film, Dazed and Confused.

The opinion was remarked upon in several online forums by members of the legal community, where debate arose over the use of mainstream cultural references in legal documents. In another opinion, issued in Pennsylvania’s Eastern District Court, a judge used Taylor Swift’s famous line to explain the way freedom of speech works:

If free speech means anything, it means that you do not get to sue people because you don’t like their opinion of you. In the immortal words of Taylor Swift, although “haters gonna hate, hate, hate . . . ,” sometimes you just have to “shake it off.”

Even Supreme Court Justices have been known to use cultural touchstones when issuing opinions. In 2020, Elena Kagan referenced both HBO’s Veep and the musical Hamilton in her opinion for Chiafalo Et Al. v. Washington. And current Chief Justice John Roberts snuck a reference to Bob Dylan into a 2008 dissent that the New York Times characterized as otherwise “achingly boring,” setting a trend for judges to slip their own favorite pop culture elements into their judicial writings.