Pop Civ 13: Lifetime Appointments for Supreme Court Justices

President Dwight Eisenhower with the Supreme Court on Nov. 13, 1953. Eisenhower appointed a total of five justices to the Supreme Court, including Chief Justice Earl Warren, on bottom left.

Introduction

“You shoot an arrow into a far-distant future, when you appoint a justice”

— President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Perhaps one of the most significant decisions a sitting president can make is the act of appointing a justice to the Supreme Court. President Eisenhower, like many chief executives, was conscious of the weight those appointments carried. Our last post explored the role of an independent judiciary within the larger context of our government. This week we closely examine one facet of the judiciary: why Supreme Court justices are given lifetime appointments. How did this tradition come to be, and what do contemporary Americans think about Supreme Court justices being offered lifetime appointments to the Court?

Lifetime Appointments to the Bench

The American Judiciary’s framework is outlined in Article III of the Constitution. Since the executive branch appoints justices to the Supreme Court, we must also look to Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 to find the constitutional framework for court appointments:

“He shall … by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law …”.

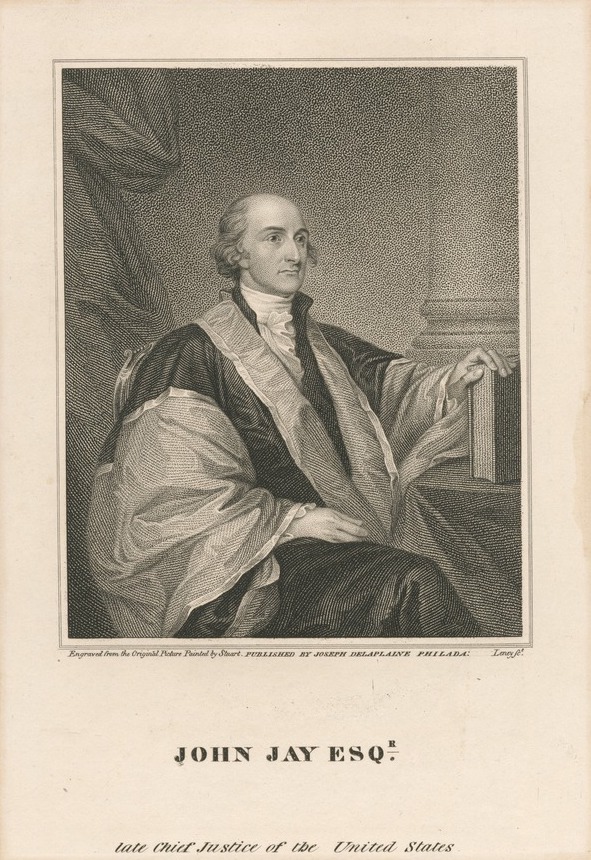

This clause empowers the president to nominate and appoint justices to the Supreme Court but requires Senate confirmation of those nominees. The first nominations for the Supreme Court were issued in 1789 by George Washington, as a result of the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789. The same day the Act was passed, Washington nominated the six justices provided for in the Judiciary Act, including a chief justice. Two days later, associate justices John Blair, James Wilson, Robert Harrison, William Cushing, and John Rutledge and Chief Justice John Jay were approved by the Senate, fully staffing the Supreme Court for the first time.

John Jay, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Courtesy New York Public Library.

A justice’s tenure is outlined in Article III, Section I of the Constitution:

“The judges, both of the supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behaviour, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services, a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.”

The phrase “during good behavior” has been interpreted to mean that a judge can remain in office for the duration of their lifetime, unless they are removed from office for misconduct, or retire from their post voluntarily. Once a judge has assumed the bench, they may hold that position for the remainder of their lives if they so wish.

The premise behind instituting lifetime appointments was to reinforce the judiciary’s role as an independent branch of the U.S. Government. In theory, by giving federal judges and Supreme Court justices lifetime tenure that exceeds congressional or presidential term limits, they are insulated from the political pressures the executive and legislative branches could exert. Additionally, a judge cannot be recalled simply because their ideology has shifted since their appointment further insulating the judiciary against political reprisals from the other branches of government. Although the theory has been tested (see our FAQ entry about Justice Samuel Chase below for an example of political pressure on a justice), the majority of the Supreme Court’s justices have been perceived as sitting above the party politics that dominate the everyday actions of members of the legislative and executive branches.

One aspect of lifetime appointments that has evolved since the turn of the nineteenth century is the shift in life expectancy. The average American was expected to live until their mid-forties in the year 1800; today’s life expectancies push well into the 70s. That means that a judge appointed to a position at the age of 40, could easily have several decades on the bench before their retirement or death. Although the founders intended to protect the Court from political influence by refusing to impose term limits on its justices, did the framers of the Constitution imagine a half-century long tenure?.

Americans have debated whether or not to amend the Constitution to impose term limits for Supreme Court justices for decades. Those who favor such reforms cite concerns about older justices’ advanced age impeding their ability to fully perform their duties and assert that justices who have served for decades are too disconnected from modern societal norms to effectively make decisions that reflect the will of the people.

Those who favor retaining lifetime appointments for federal judges and justices find any criticism of the practice to be fundamentally unconstitutional. They believe that lifetime appointments are intrinsic to the way the judiciary functions and that imposing term limits would fundamentally weaken the Court’s ability to function independently of its sister branches.

The most recent development regarding term limits came in April of this year, when President Joe Biden announced that his administration would launch a bipartisan commission to examine potential reforms to the Supreme Court. In addition to examining options like expanding the Supreme Court, the commision plans to review whether or not term limits for justices should be imposed.

Lifetime Appointments

Supreme Court Traditions and Justice Seniority

Associate Justice Amy Comey Barrett at a press conference announcing her nomination to the Supreme Court. As the most junior member of the Court, Barrett is responsible for a several tasks that are given to the newest Justices.

Imagine that you’ve just been nominated by the president and approved by Congress to a seat on the Supreme Court bench. As a member of the legal profession, you have just achieved an incredibly important career milestone. But during your first weeks in the role, you’re worrying about knocks on a door and whether the frozen yogurt machine in the Court cafeteria is working properly. Upon their arrival at the Supreme Court, the newest justice shoulders responsibilities that are reminiscent of rites of passage imposed on high school underclassmen by their junior and senior counterparts.

Generally speaking, the Supreme Court has retained a remarkable number of traditions in how its justices interact, some even dating back to the sitting of the first court in 1790. To this day, Justices are seated by seniority on the Bench, with the Chief Justice in the center. The next most senior justice is seated to their right, second most senior to their left, and so on.

The most recent appointee to the Court is, understandably, seen as less knowledgeable than the more senior justices, and is subsequently tasked with responsibilities that could easily be interpreted as opportunities to instill humility for the new justice’s role among their more experienced colleagues.

Some of these tasks involve the day-to-day operations of the Court. When the nine justices gather in conference to discuss cases, no assistants or clerks are permitted to attend, so the most junior member of the Court is responsible to respond to any knock on the closed door of the conference. Remembering her time as the least senior member of the court, Justice Elena Kagan described the experience thus:

”Literally, if there is a knock on the door and I don’t hear it, there will not be a single other person who will move. They’ll just all stare at me until I figure out ‘Oh, I guess somebody knocked on the door.'”

Other tasks are more prosaic, including the requirement that the newest justice sit on the Cafeteria Committee for the Court. During her time in that role, Justice Kagan managed to finagle the addition of a frozen yogurt machine to the cafeteria, and Justice Stephen Breyer sat on the Committee for thirteen years when there was an especially long stretch between new Court appointments.

In all, the tasks given to these new justices are designed to foster a respect for the more senior justices, but more importantly to help a strong relationship develop between all members of the Court. While a new justice may worry about making a misstep during the “Judicial Handshake,” the daily practice of shaking hands with each justice when in conference — and other similar traditions — is to reinforce the importance harmony on the Court despite ideological differences.