Pop Civ 10: Juneteenth

Introduction

As the weather turns warmer and the days grow longer, we approach a holiday that marks the end of a dark chapter in American history. Juneteenth, celebrated on June 19, is a commemoration of the emancipation of enslaved African Americans following Union victory in the Civil War.

The holiday not only encourages Americans to reflect on the realities faced by enslaved Americans but to celebrate African American culture, heritage, and resilience. Additionally, Juneteenth allows us the opportunity to examine how Americans were able to achieve new freedoms outside of the judicial system; none of the events surrounding the emancipation of enslaved Americans were made possible through the courts.

From Enslavement to Emancipation

Human enslavement had been used in the Americas since the earliest moments of European colonization, but 1619 marked the arrival of the first Africans in Virginia. While their status as enslaved chattel was not clearly defined, these twenty-some individuals represented the first of nearly half a million Africans who would be imported into North America during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Almost two centuries later, in 1788, a newborn nation ratified its freshly drafted Constitution. The document acknowledged the presence of slavery within the United States, (see PopCiv 3 about the 3/5ths “compromise” for more on this), but did not explicitly use the word “slavery” and only addressed the importation of Africans to the United States, not the domestic slave trade. In essence, the founders decided that the issue was too controversial to resolve at the time of ratification; already, southern and northern factions were sharply divided over whether or not slavery should be legal.

In 1808, the Federal government ended the importation of enslaved individuals from Africa. Even as the U.S. cut itself off from the international slave trade, domestic slave trade flourished. Northern states leaned heavily into industrialization, meaning that enslaved labor was less central to their economic model, but southern states’ agricultural economies were intrinsically linked to the enslaved labor needed to power that system.

By the late 1850s, slavery had become a powderkeg issue for an increasingly fractured nation. Southern states steadfastly wanted to protect their rights to own enslaved people, whereas northern states were increasingly in favor of abolition, some for moral reasons and others out of economic interest. The simmering tensions erupted in 1861 with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, SC, and the American Civil War was started. President Abraham Lincoln felt increased pressure from within his government to address the issue of emancipation.

The Emancipation Proclamation. Courtesy of the National Archives; transcription available here.

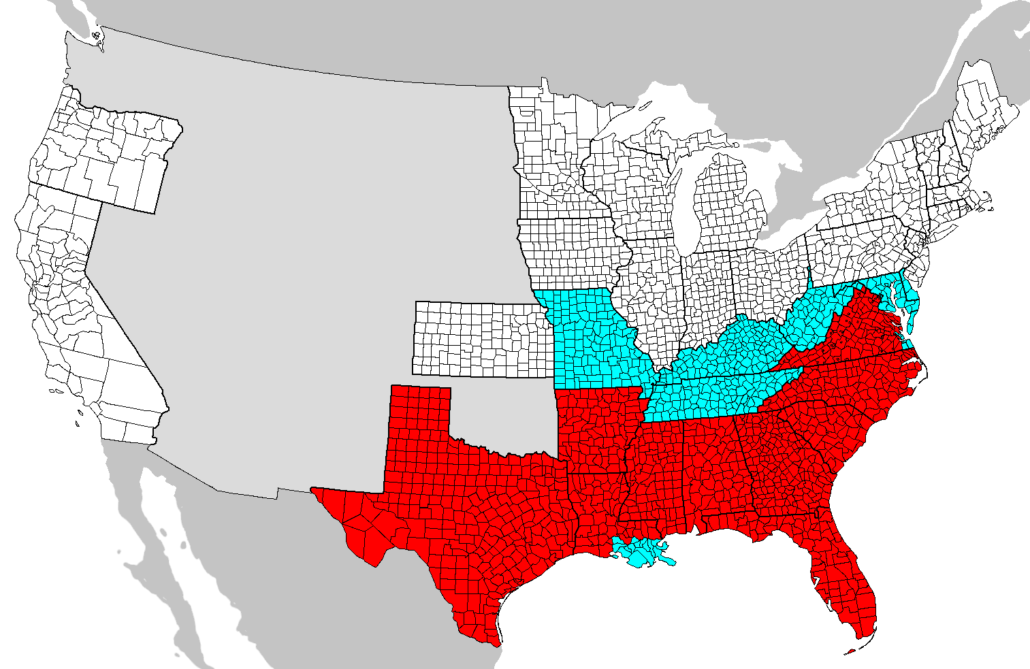

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, making it official with a public declaration a few months later on January 1, 1863. Although the Emancipation Proclamation was intended to liberate millions of enslaved people, there were limitations to who would be emancipated. First, the Proclamation only extended to enslaved persons within Confederate states that had seceded, but not those in the border states that permitted slavery. Additionally, the emancipation of those enslaved populations was contingent on Union victory; the Union could only enforce the Proclamation in regions where their troops had taken control from Confederates.

This graphic illustrates the reach of the Emancipation Proclamation; note that border states, in blue, were unaffected by Lincoln’s decree.

As the Emancipation Proclamation was made public, pro-abolition members of the Union government were at work within the legislative branch to propose a new Constitutional amendment to fully abolish slavery in the U.S. These proposals were part of broader plans for a new Reconstruction government following the end of the war, assuming the Union could pull off a victory.

By Spring 1865, a fatally weakened Confederate Army had been surrounded by Union forces near Petersburg. With Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, the Union had finally secured its victory, but at a staggering cost. More than 600,000 men were dead, including nearly 70,000 members of the United States Colored Troops, units of African American soldiers serving within the Union Army.

Although the horrors of the war had come to an end, the messy business of reunifying the nation had yet to take place. Among the five million people living in the liberated Confederate states were 3.5 million enslaved individuals; the speed with which they learned about the end of the war and their liberation varied significantly depending on where they lived.

In Virginia, for example, enslaved populations learned of their emancipation relatively quickly, thanks to the Commonwealth’s proximity to the Federal Capitol and the high volume of Union encampments. But in former Confederate states like Texas, where the wartime engagements were limited and Union presence nearly nonexistent, some enslaved populations were not aware of the surrender, let alone the Emancipation Proclamation that had been declared years before. Additionally, even though word may have reached some enslaved Texans, the Texas government staunchly refused to acknowledge federal authority and maintained their hold over their enslaved populations.

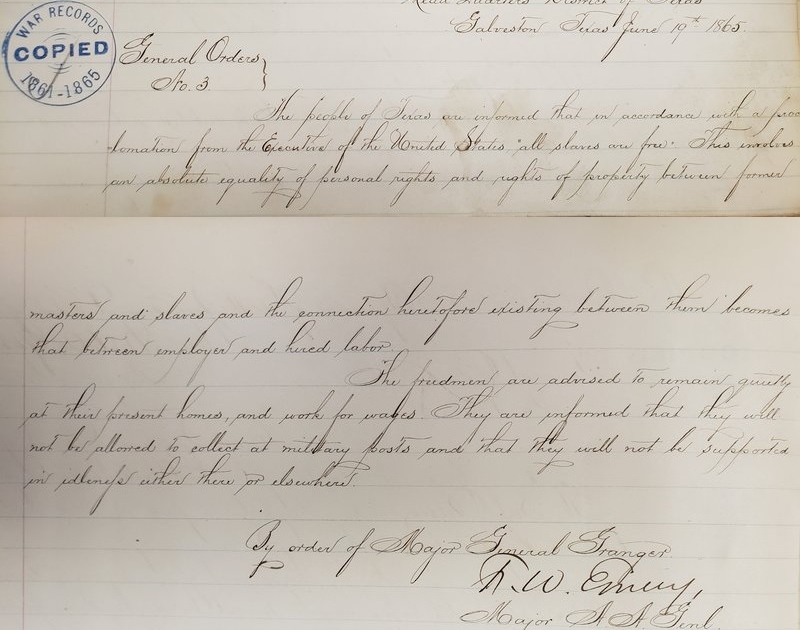

Maj. General Gordon Granger’s General Order 3. Courtesy of the United States National Archives.

By June 1865, federal troops were making their way into the furthest reaches of the former Confederacy. U.S. Major General Gordon Granger was given command of the District of Texas. Among his first actions was to have his General Order 3, outlining the news of emancipation for the enslaved population, read aloud to the public in Galveston, TX. As word spread through the enslaved community, celebrations small and large erupted and African Americans rejoiced at the news.

On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified by the required 27 of the 36 states that then existed, abolishing slavery entirely across the nation.

The 14th and 15th Amendments, establishing citizenship of all Americans regardless of race and prohibiting the disenfranchisement of voters based on race, respectively, were proposed and ratified in the years following. These three amendments came to be known as the “Reconstruction Amendments,” and are considered landmark legislation.

Each year thereafter, African American communities remembered Juneteenth (a combination of “June” and “nineteenth”) by celebrating the anniversary of the news of emancipation reaching the last enslaved populations. Life continued to be challenging for African Americans despite their newly earned freedom, with Reconstruction-era achievements and progress for people of color falling prey tot Jim Crow laws and segregation policies that proliferated in the South. Juneteenth became a moment to pause in celebration of the joy that was felt at the moment of liberation.

Emancipation and Celebration

Juneteenth Celebrations through History

When General Order 3 was read to the gathered audience in Galveston, palpable excitement spread through the crowd. That sense of joyful celebration infused all the subsequent commemorations of June 19, 1865. Beginning in 1866, Texans marked the anniversary of the Order with “Jubilee” day celebrations that included food and drink, worship services, voter registration drives, public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, and storytelling by formerly enslaved Texans.

The anniversary became an annual event for Black communities through the end of the 19th century, and as time went on, the commemorations spread to other Southern states and eventually across the country. But as Jim Crow laws began to tighten their grip on the South, African Americans felt increasingly less inclined to celebrate openly. Some local districts prohibited large gatherings of Black citizens in public parks, and in many cities, employment opportunities for African Americans were so restricted that many felt they couldn’t afford the time away from work to celebrate.

Despite these difficulties, African Americans continued to mark Juneteenth with a high concentration of commemoration taking place in Texas. In some parts of the state, “emancipation grounds” were purchased by freedmen and used as sites to host annual celebrations; in Houston, Black community leaders purchased 10 acres of land in Houston, creating Emancipation Park, which still exists to this day.

The prevalence of Juneteenth commemorations fluctuated throughout the early 20th century, but by 1980, Texas became the first state to officially designate Juneteenth as a state holiday. In 1996, the first piece of national legislation to create a federal Juneteenth holiday was proposed; those efforts continue.

Modern celebrations of Juneteenth have evolved to include new methods of commemoration but still include elements that would have been a part of the earliest Jubilee Days. In addition to local celebrations with food, music, art, and opportunities for activism, contemporary Juneteenth commemorations have included television programs like Blackish and Atlanta featuring the holiday in special episodes. As public support for a federal Juneteenth holiday grows, celebrations around the nation have grown in size and popularity.

Click to enlarge the photographs below and explore celebrations of Juneteenth around the country.