Pop Civ 9: A Year in the Supreme Court

The End of an October Term

With May drawing to a close and summer just around the corner, Supreme Court watchers are gearing up for the end of the Court’s 2020-21 term. In a few short weeks, opinions will be handed down as the Court readies itself for summer recess; the 2021-22 term will follow close behind, beginning in October. Since its inception in 1790, the Supreme Court has undergone few changes to its calendar-year and schedule, with some exceptions due to significant events like the recent Coronavirus pandemic. While we await the Court’s decision in the cheerleader free speech case (covered in PopCiv 7) sure to arrive in the next few weeks, we take a look at how this wrap-up moment fits into the broader season of the Supreme Court.

A Season in the High Court

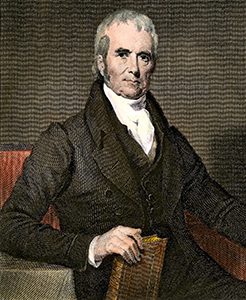

The Supreme Court has met without fail for more than 230 years, with many of its traditions shifting and evolving along with the nation in which it existed. While Chief Justice John Marshall might be disappointed that current justices would likely discourage the drinking of Madeira while debating thorny cases, he mightbe amazed at how much the work of the court has expanded in the centuries since his time as chief justice. By the early 1940s, the Supreme Court averaged 1300 docketed cases during an annual term; the typical number of cases submitted to the Court clocks in around 7,000 today. All of those cases are not heard, of course. On average, the Court will hear 100-150 cases from those submitted within a term.

The current Court’s term kicks off on the first Monday of October each year, and typically runs through late June or early July. The work of the Court is divided into two categories, sittings and recesses, which occur on roughly two-week rotations. During sittings, the justices hear cases and deliver opinions. On Monday mornings during sittings, an order list is released, outlining the court’s actions for that period. This can include reporting on certiorari decisions, updates on motions before the court, or announcements about new admissions to or disbarments from the court bar. Opinions of the Court are most commonly delivered on Tuesday and Wednesday mornings.

Recesses may seem like a more passive time for the Court, but the flurry of activity is simply happening behind closed doors. During recesses, justices draft their opinions, review petitions, and review materials related to argued and docketed cases. In addition, the Court reviews lower court decisions to determine whether any should be granted review by the Supreme Court.

Typically, the general public is permitted to attend oral arguments, and while space is limited, any individual can wait in line to hear arguments before the Court. That changed in March 2020, however, when the Supreme Court announced that it would postpone oral arguments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The business of the court continued, with the Court adapting to the pandemic by allowing oral arguments to resume via teleconference. Those precautions are still in place today, with a live audio feed of those arguments disseminated over a C-SPAN broadcast.

An example of oral arguments in a courtroom being heard via videoconference.

The public is not privy to the conferences, or discussions, between justices about oral arguments they’ve heard. These conversations usually take place on Wednesday afternoons and Fridays, and justices will often discuss cases with their own clerks before engaging with their fellow justices. When conferences occur, no one except justices are permitted . The Chief Justice calls the group to order, and justices begin to review a series of materials before them. They review that week’s petitions for certiorari and then move on to discussing the cases that they’ve heard since the previous conference.

Each justice is given the opportunity to share their views on each case, in a descending order of seniority, without any interruptions from their colleagues. After hearing from all, a vote is taken, with the first vote cast by the Chief Justice. Once the votes are counted, the Chief Justice assigns a justice from the majority to write the opinion of the Court. If there are justices who disagree with the opinion, the senior justice from that group will assign a dissenting justice to write a dissent.

Opinions are not necessarily handed down immediately after a case’s oral arguments are heard; the Court has until the last day of its term to issue its rulings. Cases in which the Court issues a unanimous decision are typically released more quickly than those where a dissent is issued. Cases in which the Court is divided often take more time for opinions to be generated, and those with controversial issues at stake can take months to decide.

As a result, there is often a flurry of of decisions handed down at the tail end of the Court’s term. As the Court gears up to release the opinions it has not yet issued for cases heard earlier in the term, the work shifts away from the hearing of oral arguments and towards increased conferences. Opinions are released every Monday in May and June, and the Court then decides upon a date to call the Court into recess for the summer. Only a few short months later, the cycle picks back up as the first Monday in October rolls around again.

The current Court’s term kicks off on the first Monday of October each year, and typically runs through late June or early July. The work of the Court is divided into two categories, sittings and recesses, which occur on roughly two-week rotations. During sittings, the justices hear cases and deliver opinions. On Monday mornings during sittings, an order list is released, outlining the court’s actions for that period. This can include reporting on certiorari decisions, updates on motions before the court, or announcements about new admissions to or disbarments from the court bar. Opinions of the Court are most commonly delivered on Tuesday and Wednesday mornings.

Recesses may seem like a more passive time for the Court, but the flurry of activity is simply happening behind closed doors. During recesses, justices draft their opinions, review petitions, and review materials related to argued and docketed cases. In addition, the Court reviews lower court decisions to determine whether any should be granted review by the Supreme Court.

Typically, the general public is permitted to attend oral arguments, and while space is limited, any individual can wait in line to hear arguments before the Court. That changed in March 2020, however, when the Supreme Court announced that it would postpone oral arguments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The business of the court continued, with the Court adapting to the pandemic by allowing oral arguments to resume via teleconference. Those precautions are still in place today, with a live audio feed of those arguments disseminated over a C-SPAN broadcast.

Supreme Court Schedule

An intern runs down the steps of the Supreme Court with the newly decided Obergefell vs Hodges opinion in 2015.

Running of the Interns

We may live in a digital age, but the Supreme Court still uses non-digital methods to share its opinions with the public. Each decision is printed and delivered to a clerk’s office within the Supreme Court building, where members of the press stand by to receive opinions. For less controversial cases, there’s no particular rush from the media to deliver that opinion to the public. But when a landmark case is being decided, the buzz surrounding the Court’s opinion can reach a fever pitch. And while networks would love to have their teams reporting live from within the Court itself, recording devices are prohibited inside the building. So how does the opinion get from the inside of the Court to the reporters on the front steps? Enter the interns.

Each media outlet has an intern stationed inside the Court, decked out in business clothes and running shoes, ready to sprint the 400 or so meters from the clerk’s office to their network’s reporter outside. In an era where a matter of seconds can mean one network’s scoop of their competitors, these interns are intently focused on getting to their teams quicker than the other interns racing beside them.