Pop Civ 7: Student Free Speech in a Digital Age

Introduction

In 2017, Brandi Levy was just another frustrated teen taking to the internet to vent about a bad day at school. The junior varsity cheerleader at a Pennsylvania high school was angry that she hadn’t been selected to move up to the varsity squad and created a Snapchat video of herself flipping her middle finger at the screen with a caption that read “F— school, f— softball, f— cheer, f— everything.” Like all videos on the Snapchat platform, the video disappeared from the app within 24 hours. Another student screencapped the clip, however, and shared it with Brandi’s coaches. Citing her use of “foul language and inappropriate gestures,” and a strict policy against “any negative information regarding cheerleading, cheerleaders, or coaches placed on the Internet,” the school decided to ban Levy from the cheerleading team.

Three years later, Brandi is at the center of a case that will be heard by the Supreme Court this week, Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. After being dismissed from the team in 2017, Brandi and her parents filed suit in district court and won their case. The school district appealed that decision, and now the Supreme Court will hear the case and determine how the details stack up against the right to free speech outlined in the Constitution. Is free speech always completely free, and should schools be able to limit speech when a student is not on school property?

UPDATE: JUNE 23, 2021

In an 8-1 decision, the Court announced today that, while schools do have a limited ability to regulate student speech, the punishment imposed on Brandi Levy did, in fact, violate her First Amendment rights. Writing for the majority, Justice Stephen Breyer explained that,

“…the special characteristics that give schools additional license to regulate speech always disappear when a school regulates speech that takes place off campus.”

Justice Clarence Thomas was the lone dissenter in the case, noting that the coach’s choice to suspend Levy was supported by 150 years of history wherein schools were permitted to discipline their students for similar infractions.

To learn more about the decision, visit SCOTUSblog’s overview of Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.

Free speech through history

One of the most important rights enshrined in our Constitution is the right to freedom of speech. The founding fathers were determined to ensure that the new nation would protect citizens from being penalized for speaking their minds, but the way in which that freedom has been interpreted in federal and local laws has evolved since the 1700s.

After the founding of the United States, Anti-Federalists grew concerned that the newly drafted Constitution would afford too much power to the central government. In an effort to protect the rights of the citizen, the Bill of Rights was created to amend the Constitution, establishing a series of rights for individual Americans. The very first item to be enshrined was the freedom of speech; that this issue was the first to be addressed indicated the framers’s desire to firmly secure the rights of citizens to express themselves without fear of retaliation from the government.

In the mid-1900s, free speech was at the heart of many debates in the public sphere. Under Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Supreme Court heard numerous cases that directly or indirectly involved the First Amendment, resulting in decisions that created the contemporary baseline for its judicial interpretation today. Unless a particular exception to the rule applies, the freedom of speech is to be protected by the Constitution, as Thurgood Marshall explained in 1972:

“… above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content. To permit the continued building of our politics and culture, and to assure self-fulfillment for each individual, our people are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship.”

The Supreme Court as it was composed between 1958 and 1962. Top (l-r): Charles E. Whittaker, John M. Harlan, William J. Brennan, Jr., Potter Stewart. Bottom (l-r): William O. Douglas, Hugo L. Black, Earl Warren, Felix Frankfurter, Tom C. Clark.

But what about those exceptions? While the right to freedom of expression seems built into the fabric of our American identity, there are plenty of instances where speech has been deemed dangerous or harmful to others. And in particular settings, the right to speak one’s mind is limited by the place in which a person happens to be.

As an example, schools are entitled to protect their students and staff against speech that poses a threat to any member of their population or that disrupts the school environment. But how does that right conflict with a student’s right to express their perspectives? And how does the advent of new technology shift those priorities?

We should note that there is a fundamental distinction between public and private school students under the First Amendment. The First Amendment and the Bill of Rights limit the government from infringing on an individual’s rights. Public school officials act as part of the government and are called state actors. As such, they must act according to the principles in the Bill of Rights. Private schools, however, are not arms of the government therefore, the First Amendment doesn’t provide protection for students at private schools.

The seminal case that established current precedent on student freedom of speech was Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a 1969 case centered around student protests of the Vietnam War. We explore the case further below, but a key difference between that case and Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L., is that the students were on school property while engaging in expressive speech. Levy was off campus when she posted her video to Snapchat. How could this detail impact the Court’s view? Also, unlike the students in Tinker, Levy was not suspended from school altogether, but was merely suspended from the cheerleading team she had disparaged, per that group’s bylaws. Does a team, sport or club have different rights than the school administration overall?

There isn’t any clear evidence from past cases to hint at which way the Court will decide in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. The case is the first instance of a social media post being evaluated within the framework of free speech, and contains so many additional details that are dissimilar to previous cases that it’s difficult to predict an outcome. Both liberals and conservatives have voiced support for Levy, even if the reasons for their support may vary. Arguments for the case were heard on April 28, 2021, which you can listen to below.

First Amendment Rights

Armbands as Protected Speech

Tinker

v. Des Moines Independent Community School District

Brandi Levy isn’t the first high school student to find herself at the center of a Supreme Court case connected to First Amendment rights. In 1965, a group of teens in Des Moines, IA, gathered in a student’s home to organize their plans for a protest of the Vietnam War. As a means of expressing their support for a truce in the War, the students decided to wear black armbands to school and to participate in a fast to draw attention to their cause. When the principals of their school were made aware of their plans, administrators drafted a policy banning students from wearing armbands to school and instituted a penalty of suspension for students who refused to comply.

In clear defiance of the rule, Mary Beth Tinker, her brother John Tinker, and Christopher Eckhardt wore their armbands to school, and were immediately suspended. Their parents filed suit against the school for restricting their childrens’s freedom of expression, and eventually the case wound up before the Supreme Court.

In a 7-2 decision, the Court ruled that the armbands were, in fact, protected under the First Amendment, and that a school was only able to limit a student’s freedom of expression if it was clear that said expression would “materially and substantially interfere” with the operation of the school. In the case of Mary Beth, John, and Christopher’s armbands, the school district could only prove their fear of a possible disruption, but had no evidence beyond that concern. In his decision for the majority, Justice Abe Fortas explained:

“It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

While Tinker proved to be a milestone for establishing the rights of students within school walls, the Court also made clear that administrators do have the right to intervene when speech becomes disruptive to the operations of the school. The question before the Court now is whether Brandi Levy’s actions fall under the latter category.

Listen to a 2019 interview with Mary Beth Tinker, where she discussed the 1965 events that led to the Supreme Court case.

Bongs 4 Jesus

Morse v. Frederick, 2007

Based on Tinker, we know that students’s freedom of speech or expression is protected by the First Amendment, but what if that speech promotes the use of an illegal substance on school property?

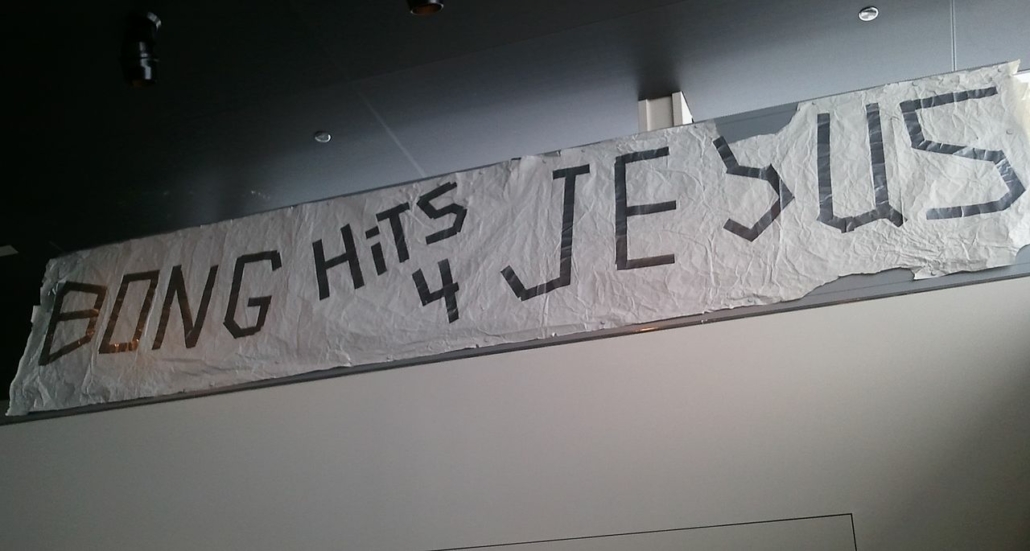

In 2002, Juneau-Douglas High School student Joseph Frederick decided to make a splash as the televised 2002 Olympic Torch Relay passed by his school in Juneau, AK. Just as television crews turned their cameras to capture the runner passing by Juneau-Douglas high, Frederick and friends unfurled a large banner reading “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS.” The school’s principal, Deborah Morse, ran across the street to remove the banner, and Frederick was suspended for his part in the event.

Frederick then filed suit, claiming that his First Amendment rights had been violated. Once the case reached the Supreme Court, the question of whether free speech on or near school property was still protected when it was related to drug activity.

Writing for the majority, Justice John Roberts explained that because Frederick was at a school-sponsored event, his speech fell under the category of “school speech,” which can be limited if administrators deem that speech to be a disruption to the school’s operation. Roberts also pointed to the reasonable assumption that Frederick’s banner was promotion of drug use, administrators could then classify that speech as a disruption to their school population.

The 5-4 decision meant that the Court was somewhat divided on this interpretation of the First Amendment. Chief Justice Roberts was joined by Justices Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito in the majority, but Justices John Stevens, David Souter, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented. The ninth Justice, Stephen Breyer, dissented in part and concurred in part. This means that he disagreed with some of the reasoning and agreed with other parts.

The original banner created by Frederick, which hung in the Newseum in Washington, D.C.