Pop Civ 3: Three-Fifths “Compromise”

Current Event

Introduction

Black History Month offers an opportunity to look at the U.S. Constitution’s Three-Fifths Clause, one of several compromises related to slavery reached in 1787 and memorialized in the U.S. Constitution. Although long repealed, these exchanges illustrate a young republic struggling to survive, while declaring the principles of freedom and equality but practicing and governing bondage.

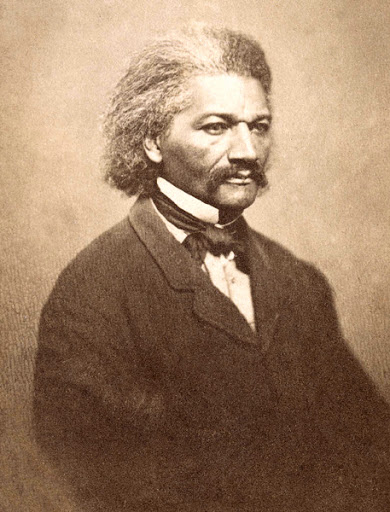

Each installment of PopCiv normally begins with a “Historical Context” section. For this one, we begin with the “Conversation Starters” section and ask a question that Frederick Douglass posed in 1860: “The Constitution of the United States: Is it Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?” It’s the name of a speech Douglass delivered to the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society in Glasgow, Scotland, March 26, 1860.

Conversation Starters

Frederick Douglass escaped enslavement and went on to become a prominent activist, author, and public speaker. He became a leader in the abolitionist movement, which sought to end the practice of slavery, before and during the Civil War.

Signing of the United States Constitution with George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Alexander Hamilton (left to right in the foreground). Painting by Howard Chandler Christy hangs in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Historical Context

Representatives from all thirteen states gathered in the Old Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia throughout the summer of 1787 to attempt to shape the government of the newly created United States of America. These 55 delegates traveled to Pennsylvania to debate the merits of various plans for their newborn government; among the issues most hotly debated was the institution of slavery.

Delegates from the South were keenly aware of the power they wielded. Their states depended on enslaved labor to fuel the massive agricultural output that made them political heavyweights; maintaining freedom around the institution of slavery was their top priority. While in the North, abolition of slavery had gained momentum.

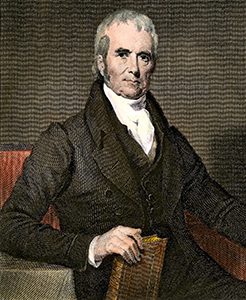

After determining that there should be a bicameral legislative branch that would include a House of Representatives with a total number of legislators based on the populations of each state, the question became how to allocate that representation. One particularly thorny aspect of the discussion was whether and how to count enslaved people when determining a state’s population, as this number would determine a state’s number of seats in the new House of Representatives. Some delegates, like Connecticut’s Roger Sherman, argued that representation should be based on the full population of a state, to include those people within the state who were enslaved. Many southerners supported this notion, but others like Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris opposed the idea, noting that southern states would be empowered to increase their importation of enslaved people to boost their power in Congress.

In the end, Charles Pinckney of South Carolina proposed what he thought to be a compromise:

“Three-fifths of the number of slaves in any particular state would be added to the total number of free white persons, including bond servants, but not Indians, to the estimated number of congressmen each state would send to the House of Representatives.”

Using the ratio that had previously been established in an amendment to the 1781 Articles of Confederation, the delegates agreed to build out their Constitution including this plan for representation. The group also provided an additional 20 years for the importation of enslaved Africans and included the “Fugitive Slave Clause,” compelling free states to return enslaved freedom seekers to their former masters. The delegates did prohibit slavery in the Northwest Territories, and there was some hope that there would be a benefit to the federal government if enslaved people were counted thus; their states would have a higher federal tax liability than if they were not counted at all. The broader questions of whether the institution of slavery was incompatible with a nation built on the ideals of liberty and justice for all were left unresolved. The Three-Fifths Compromise, however, would prove to have an outsized impact on the nation’s history for decades to follow.

It is essential to understand that, while enslaved men and women were counted as three-fifths of a person for representation purposes, they were in no way seen as three-fifths of a citizen. The early Republic had a hierarchy of rights and freedoms based on wealth, race, and gender. Landowning, and by default wealthy, white men, held the most power, and enslaved individuals the least. Neither freed nor enslaved African Americans could vote, but both groups of people were counted in the population tallies that determined how many representatives each state would receive.

In states where slavery was legal, this would account for a massive boost in how their population was tallied. For example, the 1800 Census reported that Virginia had a little over 92,000 free white residents but counted more than 345,000 enslaved people in its population. While Virginia would be entitled to send representatives to Congress based on a total of nearly half a million residents, those legislators would have viewed more than three quarters of their population as another person’s legal property rather than as constituents.

Congressional representation of southern states far outstripped that of their northern counterparts, and the ripple effect of that power was felt far beyond the Capitol Building. In their work The Constitution, Michael Stokes Paulsen and Luke Paulsen explain the southern political powerhouse:

“In effect, for every vote of a free citizen in the North, a slaveholder in the South who owned 100 slaves would have the equivalent of sixty votes. Thus the slaves states of the South consistently had one third more seats in the house than they deserved based on their free population — a huge, distorting advantage that tilted political debates in Congress decisively in favor of slaveholding states.”

In addition to their legislative power, southern states also saw an advantage in their access to the Executive branch, because that same method of accounting for population was used to determine the number of Electoral Votes allocated to each state in the Electoral College. Thirty-two of the first 36 presidents were southern slaveholders, and of course that influence extended to the judiciary, with those presidents nominating Federal and Supreme Court judges to the bench. In the election of 1800, Thomas Jefferson bumped his rival, John Adams, out of the presidency thanks to this advantage in the Electoral College. Without that southern advantage, it’s likely Jefferson would never have occupied the White House.

While the founders may have believed that their “compromise” delayed the need to make a definitive decision about slavery, their actions actually further entangled the nation in the institution. Slaveholders were empowered by the support they received from Congress, doubling down on their investment in the system and buying more enslaved people to boost their wealth; Virginia alone went from a population of around 300,000 enslaved men and women in 1790 to nearly four million in 1860.

FAQs

POP TRIV

Electoral College Today

Every four years, 538 Presidential Electors come together to cast their official votes for President and Vice President of the United States. Delegates at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 established The Electoral College, an indirect form of voting and another of the many compromises hammered out that hot summer in Philadelphia. Some delegates wanted Congress to elect the president. Others called for direct popular vote. The Electoral College is what was established with each state receiving as many electoral votes as it has members in the Senate and House. The Electoral College has been called into question for many reasons over the years, not the least of which is a reputation of being pro-slavery. The elections of 2000 and 2016 saw the nation’s popular vote lose to that of the Electoral College which has added to a movement to overhaul or do away with it.

Check out opposing viewpoints on the Electoral College, both published in the New York Times:

“The Electoral College Was Not a Pro-Slavery Ploy” by Sean Wilentz

“Actually the Electoral College Was a Pro-Slavery Ploy” by Akhil Reed Amar

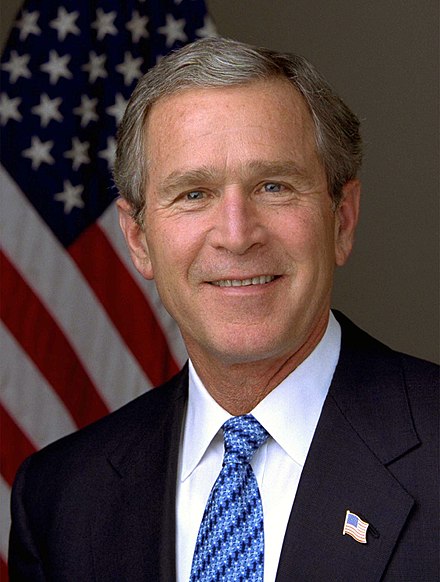

George Bush lost the popular vote to incumbent vice president Al Gore in the 2000 presidential election but won the Electoral College vote, the one that counted. It was the fourth of five presidential elections in which the winning candidate lost the popular vote, the most recent in 2016, when Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in electoral votes but not in the popular ones. Source: White House.