Pop Civ 2: Impeachment

Current Event

Introduction

The U.S. Senate will open its impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump Tuesday, February 9, 2021. It is Trump’s second impeachment trial, and the first time there has been an impeachment trial of a president who has left office. The House of Representatives impeached Trump on January 13, for “incitement of insurrection” for his role in the January 6 attack on the Capitol. A year earlier, the House impeached him for soliciting Ukranian authorities to influence the 2020 presidential election. He was acquitted by the Senate February 5, 2020, and remained in office, losing reelection to now President Joseph Biden. Only three U.S. presidents have been impeached — and none convicted: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019 and 2021, each one precedent-setting and question-raising. We, along with teachers, students and constitutional scholars alike, are reaching for the Constitution and to history for answers.

The House of Representatives impeached former President Donald Trump for “incitement of insurrection,” for his role in the January 6, attack on the U.S. Capitol. His impeachment trial begins February 9, 2021. Source: iStock

Historical Context

This upcoming impeachment trial has people asking a tough constitutional question: can a President impeached by the House of Representatives be convicted in a Senate trial if the trial takes place after he is no longer in office? While we look to the Constitution for guidance with issues like this, what do we do when both sides of an argument cite constitutional arguments for their reasoning?

Supporters of the decision to impeach President Trump look to Article I of the Constitution to support their argument. That text states that the House has the sole power to impeach and the Senate has sole power to try all impeachments:

(Article 1, Section 2)

The House of Representatives shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

(Article 1, Section 3)

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all Impeachments. When sitting for that Purpose, they shall be on Oath or Affirmation. When the President of the United States is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no Person shall be convicted without the Concurrence of two thirds of the Members present.

The basic argument here is “all” means “all.” The House impeachedTrump while he was president, so the Senate has the power to hold a trial.

But those opposing the impeachment trial cite another section of the Constitution’s text in making their case. In Article II, the Constitution specifies that an automatic consequence for being convicted by the Senate in an impeachment trial is removal from office:

(Article 2, Section 4)

The President, Vice President and all Civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

If the Senate convicts a president, that President must be removed from office. Of course, you cannot remove a President from office if they have already left the presidency. By that logic, you can’t convict a President in an impeachment trial if they are no longer in office.

One approach to better understanding the two sides of this debate is to look at the history of our nation, and try to understand how the founders might have looked at this issue.

An argument in favor of impeachment is the fact that the founders were particularly fearful about the possible danger a demagogue could present to the sanctity of constitutional rule of law. During the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Washington, Mason, Madison, Hamilton, and others expressed their concerns that a charismatic but autocratic leader could incite the public into overthrowing the government they were so painstakingly trying to establish. The inclusion of text outlining the process of impeachment was their answer to those worries. While a member of the Convention might not be able to envision a President whose Twitter account had millions of followers, some argue that they would have easily found Trump’s rhetoric to be inflammatory.

On the flip side, others believe that the founders would have considered the trial and conviction of a former president to be an example of governmental overreach. In structuring the Constitution with clear checks and balances for each of the three branches of government, the founders sought to ensure that the judicial, executive, and legislative branches would each be prevented from overstepping the boundaries of their corners of the government. By pushing forward with an impeachment that isn’t clearly mandated by the Constitution, some argue that the legislative branch would be pushing beyond its rightful jurisdiction.

We don’t claim to have an answer to this thorny debate, but rather encourage you to make your own judgement about the cases presented by both sides of this argument. While it can feel frustrating to be without direct answers from the Constitution itself, this ongoing interpretation of that document is part of the founders’ plan for a government that would evolve and adapt along with a growing nation.

For additional information, the links below will take you to longer explanations of the case for or against the impeachment of President Trump.

PRO

Keith E. Whittington, Princeton University

Can a Former President Be Impeached and Convicted?

Frank Bowman, University of Missouri School of Law

Constitutionality of Trying a Former President Impeached While in Office

ANTI

Philip Bobbitt, American author

Why the Senate Shouldn’t Hold a Late Impeachment Trial

J. Michael Luttig, American lawyer

Opinion | A Senate impeachment trial after Trump leaves office would be unconstitutional

FAQs

While we can’t provide a definitive solution to the question of whether or not the trial and conviction of President Trump is constitutional, we can look to some concrete facts about how the Constitution outlines the process of impeachment:

POP TRIV

American presidents and their acquittals, near impeachments, resignations, and second helpings

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, the first sitting president to be impeached, came under fire for his removal of Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War, from the United States Cabinet. After taking office following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, former Vice President Andrew Johnson supported Lincoln’s plan for a lenient path towards Reconstruction in the South. This policy included amnesty for Confederates who agreed to sign an oath of loyalty to the United States, a particularly contentious issue among the radical wing of the Republicans.

In addition to those in Congress who strongly opposed Johnson’s plan, some of the members of the Cabinet that Johnson inherited from the Lincoln administration also voiced their opposition. Conscious of the risk that those who opposed Johnson could be removed from their positions of power, Congress passed The Tenure of Office Act in 1867, requiring that the president seek Congressional approval before removing officials from their offices. That same year, in full defiance of the Act, Johnson replaced Secretary of War Edwin Stanton with Ulysses S. Grant, hoping to have a political ally in the role to help move his Reconstruction plan forward.

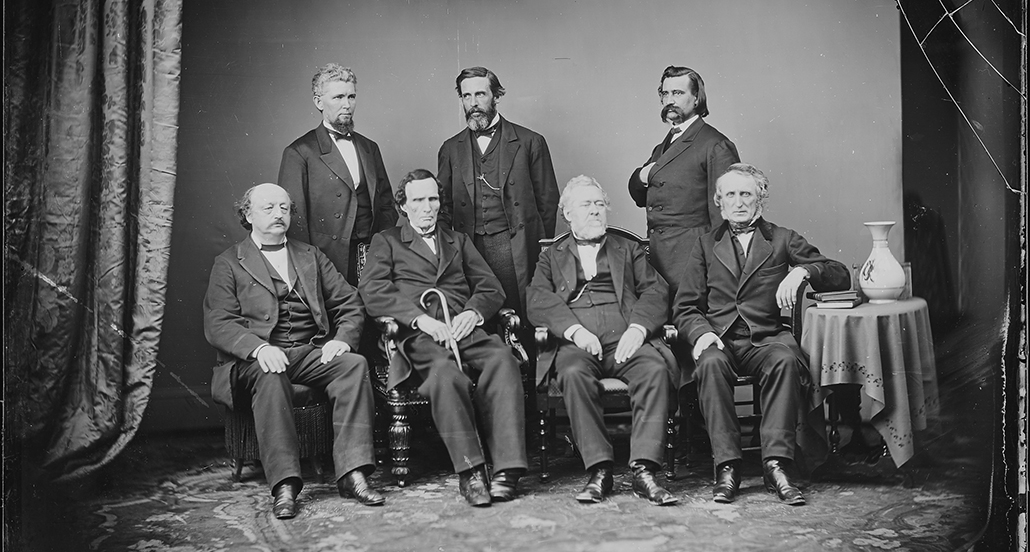

After hearing the furious response from Congress, Grant ceded the position back to Stanton, and the House moved forward with Articles of Impeachment against Johnson. The House impeached Johnson on February 24, 1868, and the Senate trial that followed lasted from March to May of that year. Johnson was acquitted by a narrow margin but was vindicated decades later; in 1926, the Supreme Court ruled that the Tenure of Office Act was invalid.

Andrew Johnson Impeachment Committee: Hon. George S. Boutwell, MA, Gen. John A. Logan, Hon. Thomas Williams, PA, Hon. James F. Wilson, IA, By Matthew Brady. Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

President Richard Nixon and his resignation from the Office of the President. Source: White House

Richard Nixon

President Richard Nixon resigned before his impeachment trial took place. The blockbuster book All the President’s Men, tells the events that led to his resignation. When the Watergate story was still unfolding, Robert Redford contacted The Washington Post reporters covering it, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, to express his personal interest. The reporters didn’t take a meeting, but Redford said something that stuck with them. He said the most interesting way to tell the story would be to lay it out piece by piece, in the order they uncovered it. He recommended making their narrative a procedural, like a detective story. Woodward and Bernstein disagreed at first, not wanting to insert themselves into the news but soon came to realize Redford was right and followed his approach when they wrote the book. “He laid the seed for that in that first phone call,” Woodward later said. Redford would later produce and star in the film adaptation.

Source: IMBD

Bill Clinton

While President Bill Clinton was acquitted by the U.S. Senate of lying under oath and obstruction of justice, he soon after faced civil litigation for contempt of court, illustrating the distinction between a political impeachment tribunal and the role of traditional courts. In April 1999, about two months after being acquitted by the Senate, Clinton was cited by a federal district judge for civi contempt of court for his “willful failure” to obey her orders to testify truthfully in the Paula Jones sexual harassment lawsuit, a resulting discovery from his impeachment testimony. He was assessed a $90,000 fine, and the matter was referred to the Arkansas Supreme Court. On the day before leaving office, Clinton agreed to a five-year suspension of his Arkansas law license and to pay a $25,000 fine as part of an agreement to end the sexual harassment investigation without the filing of any criminal charges for perjury or obstruction of justice. Clinton was automatically suspended from the U.S. Supreme Court bar as a result of his law license suspension. He resigned from the Supreme Court bar during the 40-day appeals period. He reached a civil settlement with Paula Jones, agreeing to pay her $850,000.

Donald Trump, second impeachment trial

U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts and Vice President and Senate President Kamala Harris both declined to preside over the second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump. Senator Patrick Leahy, President Pro Tempore of the Senate, will preside.

Lesson Plans

Click on the links below for lesson plans.

Lecture

What is the Chief Justice’s Role in Impeachment?

Welcome and introduction by W. Taylor Reveley III, President Emeritus of the College of William & Mary, featuring Michael Gerhardt, Samuel Ashe Distinguished Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of North Carolina and author of Impeachment: What Everyone Should Know, who testified in President Donald Trump’s first impeachment trial, and Henry L. Chambers, the University of Richmond Austin E. Owen Research Scholar & Professor of Law.

Presented by the John Marshall Federal Courts Program, a partnership of William & Mary Law School, the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, and the John Marshall Foundation. Sponsored by the Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

JMC 2021

JMC 2021