Pop Civ 20: West Virginia v. EPA

Introduction

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 30 ruling in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) greatly restricted the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) regulatory powers,setting a limiting precedent for other regulatory agencies. By way of a 6-3 vote, the Court decided that any time an agency takes regulatory initiative outside of their “normal” range of action, that regulation is invalid unless Congress grants the agency permission to conduct that particular action in a new field. This new development makes us wonder – how has America wrestled with the debate over regulation versus growth of industry, and how does the Supreme Court’s recent decision impact the autonomy of regulatory agencies?

Historical Context

Since our nation’s founding, Americans have argued over how to protect our nation’s natural resources while still affording industry space to grow. Beginning with the Rivers and Harbors Appropriation Act of 1899, which made it a misdemeanor to knowingly pollute, excavate, or alter navigable waters of the United States without a permit, the nation has enacted state and federal laws to help protect the environment. Many agree the most consequential environmental law is the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), passed by Congress January 1, 1970 after a decade of rising public concern about the effects of industrial growth on the environment. The Nixon Administration was also influenced by this growing worry and issued an Executive Order creating the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970, reorganizing resources from several other federal agencies. In the years that followed, a series of regulatory laws were passed by Congress formalizing the EPA’s authority to regulate various industries in pursuit of environmental protections.

Since the 1970s, the EPA has taken measures to reduce the impact of human industry on environmental resources. In 2014, the Agency recommended that the Obama Administration implement the “Clean Power Plan for Existing Power Plants,” (CPP) which would phase out fossil fuels used in power plants in favor of newer energy sources that produced fewer carbon emissions. President Barack Obama, in partnership with the EPA, announced that it would implement the CPP in 2015. One particular fossil fuel in the plan’s crosshairs was coal; any coal-burning power plants would be required to shift first to burning natural gas, and then to renewables like wind or solar power.

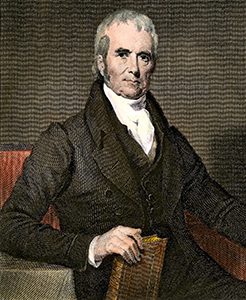

President Nixon signs the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) on January 1, 1970.

In order to accommodate the recommended shift in the composition of the energy supply, the EPA expected producers to reduce their plant’s production of electricity, build, invest in a new or existing natural gas plant, wind farm, or solar installation, or purchase emission allowances or credits as part of a cap-and-trade regimen. If energy-producing firms followed one of these emission-reducing pathways, the EPA expected that a fundamental shift in the structure of the American electrical grid would occur, which, it argued, would have a sizeable impact on the reduction of carbon emissions. The EPA claimed its authority to create these regulations from a section of the 1963 Clean Air Act, which directed the EPA to determine the “best system of emission reduction” for power-generating sources.

In August of 2015, however, 28 states and hundreds of private companies filed suit in the Washington, D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals challenging the legitimacy of the CPP. Among their complaints was that the EPA overreached its authority, and in February of 2016, the Supreme Court issued a stay via the Emergency Docket, preventing the CPP from taking effect. The CPP’s implementation was further delayed in 2017 when the Trump Administration took power and vowed to repeal the Plan as soon as possible. In August of 2018, the EPA issued the Affordable Clean Energy rule (ACE), which had the effect of repealing the CPP. In 2019, the ACE rule was published, and almost immediately challenged in court by organizations like the American Lung Association and the American Public Health Association. Eventually, a series of cases (Westmoreland Mining Holdings, LLC v. EPA, North American Coal Corp. v. EPA, and North Dakota V. EPA) merged together to be heard by the Supreme Court as West Virginia v. EPA.

In a June 30 decision, Chief Justice John Roberts authored the majority opinion reversing the lower courts’ decisions, decreeing the EPA had no authority to set emissions caps with its Clean Power Plan. In his concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch further explained that regulatory agencies had no power to apply such a systemic approach without being explicitly directed by Congress to do so, referring several times to the “major questions doctrine.” (Click here to learn more about the background of this legal concept.) [SEE BELOW FOR PDF TEXT]

Justice Elena Kagan issued a dissent and was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Sonya Sotomayor in strongly rejecting the interpretation of the majority. In her dissent, Justice Kagan accused the court of creating new rules that defy decades of precedent in the regulatory space. Claiming the Clean Air Act was written with adaptability in mind, given that the energy industry is constantly changing, Justice Kagan argued that the ambiguous language of the law was intentional and would allow the EPA to regulate new issues in the power sector as they arose. Furthermore, the dissent points to an overstepping of power in that the Court:

“ … does not have a clue about how to address climate change … yet it appoints itself, instead of congress or the expert agency … the decision-maker on climate policy. I cannot think of many things more frightening.”

Regardless of whether they cheered or condemned the decision in West Virginia v. EPA, Court followers agree that this opinion will have an impact beyond the ecological sphere. In addition to federal regulatory agencies being required to bolster their authority with clear legislative language, there is a sense that rules with wide-ranging economic consequences are more likely to meet court scrutiny.

A 2022 list generated by The Yard, a British PR company, highlighted the carbon footprint created by celebrities like Travis Scott, Kim Kardashian, and Taylor Swift, among others.

Pop Triv

While the Supreme Court’s decision in this case West Virginia v. EPA has serious legal and constitutional implications, the nation’s focus on environmental regulations reaches far beyond our courts. As summer temperatures reach record levels around the world, the is a growing sense of urgency to scrutinize personal consumption of fossil fuels. And even the most beloved celebrities are not beyond criticism leading lavish lifestyles that could negatively impact the environment.

In early August 2022, the UK-based digital marketing company Yard issued a report that listed public figures with the highest carbon emissions, based on data culled from a popular twitter account that tracks celebrity private jet use. Among the worst offenders were Taylor Swift, Travis Scott, and Kim Kardashian. The Yard list generated significant buzz by highlighting the impact individual use of private jets on CO2 emissions, and some of the figures on the list issued statements defending their actions.